The view from the Hattan Family farm. Up on the higher slopes of the dales, traditional Wensleydale country.

The view from the Hattan Family farm. Up on the higher slopes of the dales, traditional Wensleydale country.

The bulk of this was written a couple of years ago and revisited recently. I made cheese with the Hattans when I was working for the Courtyard Dairy in 2015/2016.

Andrew Hattan and his wife Sally, farm up at Low Riggs in the high dales above Middlemoor near Nidderdale. Their farm is up at the top of the Dales and literally off the beaten track. The tarmac road ends at Middlemoor where there’s a car park where Andrew or Sally will meet you to take you the rest of the way in their 4×4. The track consists of concrete slabs, fording the odd stream, dirt tracks and winding past other farms, now deserted, but formerly working farms which used to produce Wensleydale cheese.

Andrew and Sally are part of an EU scheme restoring the area to its former fertility as it had been over grazed by sheep farmers in the past 20 years. They have a grant for re-planting their pastures with herbs and flowers that would naturally have grown at that altitude. They farm sheep which makes sense as they are hardier than cows but part of their grant means they have to also farm cows. The only cows which really can produce milk from that sort of pasture, which while rich in herbs, flowers and interesting plants is low in rich, leafy grass, are Northern Dairy Shorthorns, the traditional breed of that area and of the Lake District and Lancashire.

From a retailer’s perspective, their cheese has the potential to be a marketing dream. The closest to alpine pasture that the UK can find, a rare breed of cow that produces the milk, not to mention that their plan is to make an unpasteurised cheese, ultimately using starters manufactured from their milk and allowing it to blue naturally rather than introducing mould cultures. It all adds to something you desperately want to sell.

To their credit, the Hattans are taking this slowly. They can make the farm work financially with their sheep farming, although they are becoming less and less satisfied with it. They have yet to get approval from their EHO. But they have begun to make the odd batch of an old fashioned Wensleydale recipe cheese and thanks to Sally’s experience in the NHS equipping her to interview people in a sensitive way, they have managed to catalogue some fascinating interviews with local ladies, now in their 90s, who made Wensleydale back in the pre 2nd world war days when cheese was still made on the farm.

Until they are ready to get the Environmental Health involved, they make cheese in a utility room off their kitchen. The plan is to convert that room and a couple of rooms that adjoin it to cheesemaking space within the house. They have a couple of catering bain-maries which stand in place of steam jacketed vats, currently and use an old cheese press that Andy Swinscoe loaned them. For the moment, the curd is broken by hand rather than with a curd mill.

Andy and I spent a day with Andrew, Sally and their kids to make cheese, last August. They had kept the milk from a couple of days milking to make their cheese. Their neighbour currently milks their cows. His farm is a bit further down the valley and actually has a milking parlour where their farm has been extensively grazed for sheep. They put 4 cows through his parlour and save up 2 days milking to make cheese. It makes a couple of cheeses a batch. We are not yet talking about serious production but given time, we could be talking about something interesting. We had met them previously at Graham Kirkham’s where they were asking him about farming, milking and feed. This time we were coming to help them with a cheese make and suggest ways they could improve consistency and tailor it to the more open textured cheese they hope to make.

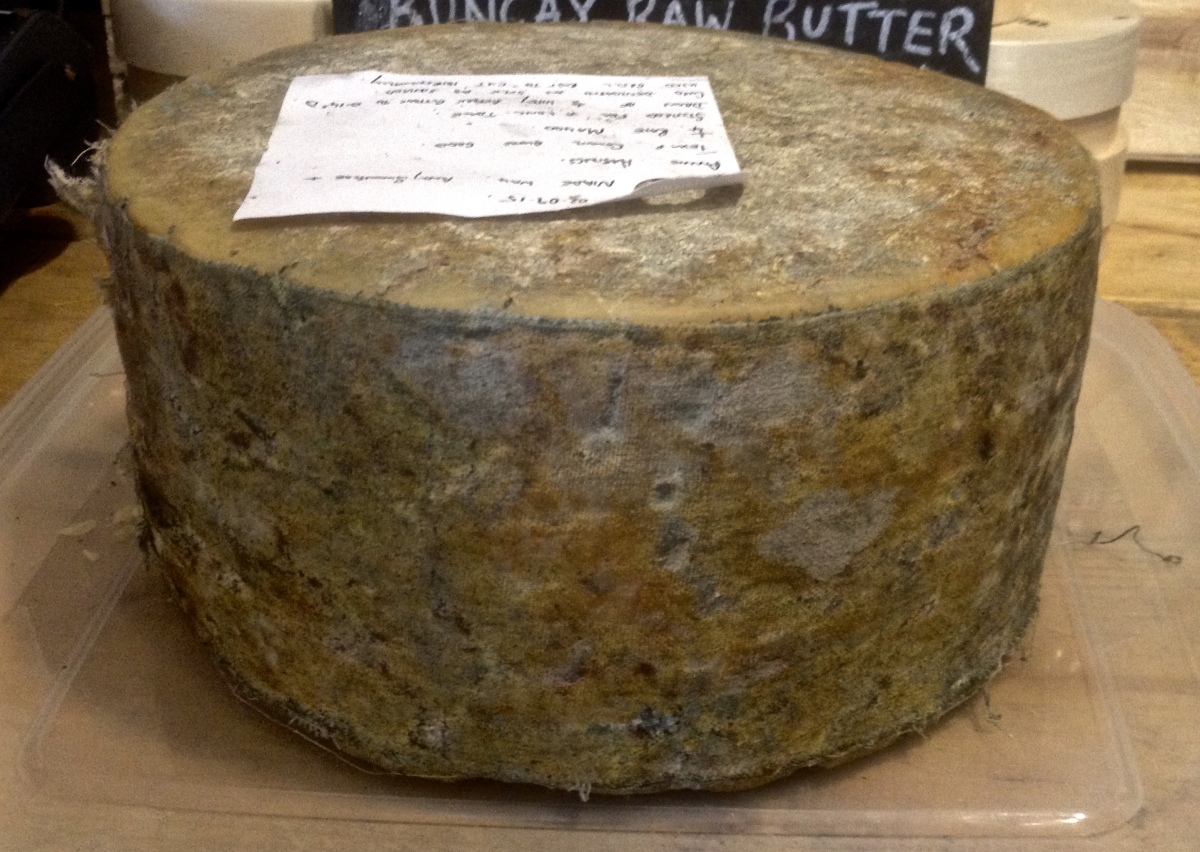

They heat the milk in the bain marie and add starter cultures. When we visited them, they were using DVI cultures which are easy to use and get started with but in the following months, they began to experiment with cultures from Barbers. They tried MT36 which is beloved by Joe Schneider for his Stichelton, Martin Gott for St James, Todd & Maugan Trethowan for Gorwydd Caerphilly, Sam Holden for Hafod and also Charlie Westhead for his Finn cheese and is known to produce a great depth of buttery flavour in different types of cheese. However their preference initially was a different Barbers’ starter, recommended for creamy Lancashire production, ML69, whose flavours they felt better suited the sort of cheese they wanted to make. After acidifying, adding rennet and cutting the curd to 1cm cube, the curd is stirred gently while heating slightly and then whey is run off. The curd is then allowed to rest, cut into blocks and stacked on top of each other to further assist drainage. The drained curd at a set acidity is then broken up (currently by hand into walnut size) and salted before being packed into a mould and put into the victorian cheese press that Andy leant them. It stays there overnight before being removed from its mould, turned and transferred to their maturing room. And from there it’s a anyone’s guess including their own. Currently their cheeses have been a bit too dry textured and therefore close textured to allow blue to develop. As they change starters and therefore the acid profile changes, the texture of a cheese will also change. While it may may not have worked as of August 2016, things are changing.

The last I heard from the Hattans, with the help of the Specialist Cheesemaking community and no doubt Neal’s Yard Dairy as well as the Courtyard Dairy, they are in production and selling cheese at their farm Open Day. Andrew had spoken at the Science of Artisan Cheese Conference in 2018 on milk production and I’m sure he was a fascinating speaker. The years have moved on since I made cheese with them but I hope to be buying their cheese soon. The ones I have seen do not as yet appear to be blue. It may happen, it may not. I think ultimately the milk and the make dictate your cheese whatever you wanted it to be initially.