‘What do you know?’ asked Graham Kirkham, on meeting me in the dairy.

‘Um – not much?’ I ventured. But I was about to learn a lot.

The really exciting thing about the Kirkhams, from my then perspective as a retailer and temporarily disadvantaged cheesemaker is that they farm only with their cheese in mind. They have no Dairycrest contract to fulfil, no minimum litres to achieve and therefore everything about how they farm has the goal of making amazing cheese.

Amazing cheese needs amazing milk but, specifically, it needs cheese-orientated milk. This means that it needs to have zero pathogens but viable lactic acid bacteria and good solids (fats and proteins). Graham’s cows are largely Friesian which would normally produce milk with about 3% fat. His cows manage 5% fat. For comparison that is Jersey milk levels.

They achieve this by specifically gearing the feed and breeding so that it suits the rhythms of the cheese. They stagger the calving all year round so that the milk is consistent in quality. End of lactation milk has different fats and proteins and tends also to have a higher bacterial load. Early lactation milk has a tendency for the fats to separate out more easily as well as also having a higher bacterial load. The more you can balance out these inconsistencies, the easier it is to make good cheese. The cows are fed silage all year round in addition to the pasture that they graze. In fact, last year (it was September 2015 when I visited), although they had free access to the outdoor pastures, the cows had been happier indoors where they have an airy barn with a back scratching brush roller. It had been monumentally rainy in Lancashire that summer. This meant they had eaten more silage than usual and the milk was more consistent.

The grass, being open to the air, varies. Variety can come from moisture content one rainy day to the next drier day as well as having higher sugars at the beginning of the season and more fibre towards the end of the season. When cutting grass for the silage, the Kirkhams wait longer than the average dairy farm. If you’re farming for milk production, you want fresh young grass, high in sugars and plenty of moisture. It’s rocket fuel for volume production. But if you’re looking at the solid content of the milk rather than the number of litres you’re producing, you’ll cut your silage grass later in the season when it’s more fibrous. This helps the fat percentage in the milk and is probably one of the reasons that the Kirkhams are able to make a Friesian herd give Jersey quality milk.

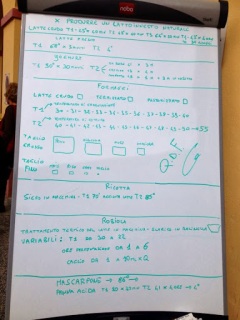

The reason they go to all this trouble with the milk is evident when you look at the way they make cheese. In the interests of achieving the correct buttery crumbling texture and slow acid development, they use tiny amounts of starter. For a vat of 2,500 litres milk they use milliletres of starter where a quicker recipe would call for 25 litres of starter or 1% of the milk volume. As a result of their starter use, they have a slow acid development, which helps the curd develop a richer, more nuanced, complex and subtle flavour that will develop over time. They mix the curd from 2 days production together when it comes to moulding cheeses so this slow development is what allows them to do this without compromising the flavour of the final cheeses. It is the traditional way of making Lancashire, dating back to when cheese would have been made without starter or at least using the whey from the previous day’s make as starter if necessary. Those were days in which cows, being milked by largely by hand, had more lactic acid bacteria in their milk so the need for starter cultures was reduced.

The cheeses are made over 2 days. On the first day, the milk is pumped into the vat and starter is added. They use a liquid starter, which looks like a runny yoghurt and tastes pretty delicious. The rennet is added about 20 minutes later, giving the starter time to acclimatise to its new medium but not develop appreciable acidity. The set is intended to take about an hour and, as they are practised hands at this, it does. The curd is then cut to the size of a hazelnut or roughly a 1cm cube. It is stirred briefly before it’s allowed to settle. Greater stirring would increase the acid production and create a bright and dry crumbly curd, which isn’t the mellow buttery, feathery texture Graham is going for. After about an hour, the free whey is pitched off and the settled curd is ladled into the centre of the vat, where the pressure of each new ladle of curd helps the curd-mass squeeze out whey.

When there are empty channels at every edge of the vat, the curd is allowed to bow out under its own pressure and then using a knife, blocks of curd are cut and stacked onto the curd mass continuing the whey expulsion. Finally a channel of curd blocks is cut into the centre of the vat and from then they begin to handle the blocks of squashed curd onto a cloth lined draining table. During this process, the curd has changed from a soft and jelly-like texture to something more akin to chicken breast. Once in the draining table the curd is broken by hand into pieces that roughly equal a handful of curd and then left to drain for an hour with the cloth wrapped around them and light weights placed on top to ensure the whey doesn’t stop draining.

The curd is broken again another 2 times during the afternoon with an hour’s wait in between each break. The time between curd breaks will then be used to combine a couple of days’ curd, mill it, salt it and pack it into moulds, which will form the final cheeses. It smells utterly delicious at this stage. In fact it’s one of the best jobs of the day, arm deep in curd that smells of lactic butter and, if you sneak a taste, tastes of salty, buttery gorgeousness.

A mixture of blocks of curd from yesterday and the day before are put through the curd mill to bring them down in size. Salt is then added and mixed by hand before the curd with salt is milled a further 2 times and then when it’s a fine texture, is packed into moulds and put into the presses overnight. The presses are tightened slowly with Graham doing the final turn at about 9pm – you don’t want to press the curd too soon or it might actually make the surface too firm while the interior retains its moisture. This would lead to funky fermented flavours as trapped moisture and naturally occurring yeasts go crazy together at a cosy temperature of about 20C. It’s especially likely to occur if you try and mix curd from 2 days as one lot of curd has sat for an extra day at ambient temperatures and without any salt to slow down yeast and bacterial activity. This makes the yeasts sound undesirable and as long as they are controlled and in balance they certainly are not. They are part of the natural flora of the milk after all. The key is balance and control thus it’s important to keep an eye on the drainage and pressing of the curd. Why bother with 2 day curd if it’s so much more difficult? The 2 day curd is important because it creates a mellow, buttery, savoury and complex flavour and this is something that sets the Kirkhams apart from other Lancashire makers who have opted for the faster and moister way of making cheese. On the face of it, it makes sense commercially to have a shorter working day and a fast maturing cheese but then by following the slower and more traditional route, the Kirkhams have a unique and delicious cheese that is highly sought after. Its popularity and the satisfaction in tasting the cheese alone justifies the considerably greater workload that it requires but because it is something special, Graham can also charge a price that means despite the slower maturation, greater workload and indeed resulting wage bill, he can make a profit. This is the way of artisan cheese. If you listen to conventional business theory, it makes no sense and yet if you stick to your guns and make something really good, it makes money. Goes to show the limitations of what we normally see as business sense.

If Graham made a ‘more efficient’ cheese, the curd would be too wet to keep for an extra day. If he tried to then it would taste eggy, sulphurous and so the quicker and moister recipe tends to lend itself to a simple one day curd cheese. This is fine but one dimensional and lactic , whereas the addictive quality of Kirkhams is that it has so much more than that. A few days in his dairy and I learned about milk production, cheesemaking and had a beautiful illustration of the shortcomings of the standard business model.